Making money grow on your post-graduation decision tree

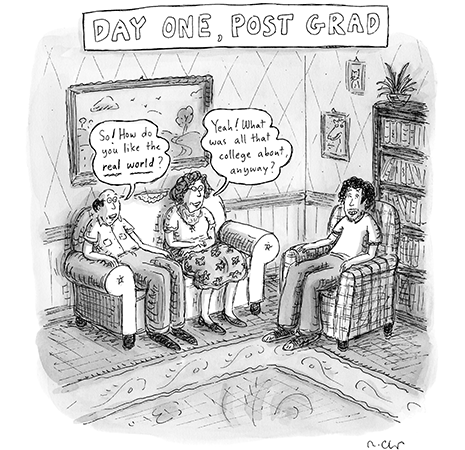

Congratulations! You’ve just completed an undergraduate degree, and all those 9.00am lectures, 5.00pm deadlines, and 3.00am cups of tea as you crammed for the last exam are behind you and it’s time for the next step. (If you’re still in the middle of your exams, please re-read in a couple of weeks.) You’ll eventually want to find a job, and you’ve come to the right place, but unfortunately it might be necessary to get another degree first. Here are some things to think about as you think about what to do next.

Work or study?

The first choice is between work and further study, which is essentially a choice between money now and money later. There’s consistent evidence that lifetime earnings are higher for people who are better educated, but postponing the start of your career means you’ll be broke for a while. If you choose to work, there are now more possibilities than before, but more is not always better. The alternative to a paid jo these days is an internship, a job in everything but salary. They’ll sell it to you on the basis of the experience you’ll gain and the contacts you’ll make. Depending on how wealthy your parents are, an internship might be possible, but the principal that people should be paid for the work they do is an important one.

Choosing to study also involves two options with more or less investment and commitment: Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) or conventional university degrees. You can MOOC up fairly quickly and take your chances job-hunting on the wide open plains of the internet. An alternative way of thinking about the next level of learning is to consider the skills with which you’ll be equipped by the end. You can get a primary degree if you can count your own toes and spell juxtapose but further study should about independent work, critical thinking, project management. Post-graduate courses are also necessarily more specialised than primary degrees. While it’s not impossible to change direction later, a post-grad course is the first step in a new direction.

Master’s or PhD?

As for degrees, there are millions of courses in economics and related areas in universities around the world. Some of them are probably rubbish, most are likely to be great, and there are certainly a few amazingly good ones, directed by genii with gold-leaf white-boards and one hundred percent graduate employment rates; in other words, the quality of post-grads courses is normally distributed. Keep that in mind when you’re looking at your options, and just try to avoid the rubbish ones. PhDs, still that tallest of the post-grad mountains, are a tricky business: they used to be a qualification to teach in university but, with the inflation, it’s just a longer Master’s.

If you’re brilliant enough that your supervisor or lecturer is really keen for you to sign up for a PhD, to stay on and work with them, then there’s a different kind of decision to make. Academics secure funding for research and then have to secure people to do it. The easier thing for them is to pick the student at the top of the class, that is, the top performer not the one who sits in the front row wearing a love-struck expression; the top students are already familiar with the department, the university, and the town, and they’d do a really good job. The choice for the start student is whether to continue in comfortable familiarity or, if they’re so brilliant, try to do better elsewhere. It’s nice to be wanted but think carefully about whose interests are being served.

The transition from college to work is more difficult than moving from under- to post-grad. For all that your lecturers, tutors, and supervisors pretend to be interested in what you do, your boss makes or loses money depending on what you produce, so there’s no pretence. Office culture is also different from class culture. It’s possible that you’ll be the only economist there, meaning that you’ll have to spend some time explaining things, as well as making a case for the value of your perspective.

Career change?

It’s a tiring business to weight up the merits of work, then paid or unpaid, versus study, whether short-term or long-term, to say nothing of thinking about a career change. Statistics show that you’re probably better off with more qualifications and, while the future is uncertain, the probability of a successful career is high. For now, though, just look forward to the graduation ceremony and don’t forget to take your parents out for dinner afterwards.